Vulnerability in writing memoirs. It's a real thing, trust me.

You’ve gone through the agony and ecstasy of writing your memoir, revised it until you're sick of the sight of it, had it proofread, and it’s as good as it’s ever going to be.

Now it’s time to publish it.

Publishing a memoir is scary. Not as scary as base jumping or waterfall kayaking, but it’s all relative.

There would probably be some who’d rather do those things than publish a memoir – if they lived long enough.

Publishing a Book is Like Being Naked in Public

A well-written memoir includes not only events, but thoughts and emotions. It’s your emotional journey that gives it depth and meaning, and allows readers to see you as a real and authentic person, and relate to you and your experiences.

But it can be scary because you don’t know how they’re going to react, especially if you’ve chronicled some of your unkind or weird thoughts, extreme emotions or bizarre behaviour.

You’re worried that people will think you’re crazy – or even worse, a horrible person.

Poet Edna St Vincent Millay famously said, ‘A person who publishes a book appears wilfully in the public eye with his pants down.’

Even more so if you’ve written a memoir – like those dreams you had as a kid about turning up to school stark naked. (Or was that just me?) If you’re writing fiction, you can hide to some extent behind your characters, but your memoir is all about you, so there’s nowhere to hide.

It's All About Vulnerability

I can empathise completely with you, because having written and published my own memoir Making the Breast of It, about my breast cancer journey, I know that feeling of trepidation.

It’s all about being vulnerable. The dictionary defines vulnerability as ‘the quality or state of being exposed to the possibility of being attacked or harmed, either physically or emotionally.’

As a writer it’s not so much fearing readers coming after you with an axe, it’s the verbal and/or emotional fallout – criticism, judgment and rejection.

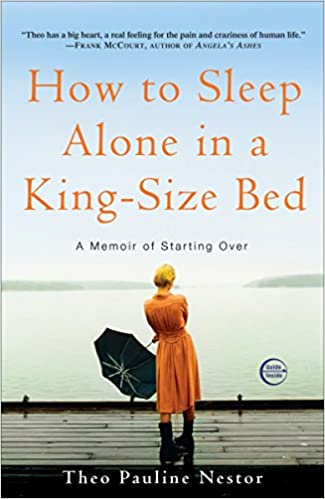

In her blog post How To Be Vulnerable When Writing Memoir, acclaimed memoirist Marion Roach Smith introduces us to Theo Pauline Nestor, who wrote Shame, Vulnerability and the Art of Writing Memoir, and How To Sleep Alone in a King Size Bed.

The Most Compelling Memoirs

Nestor says, ‘The memoirs we find most compelling and evocative are generally the ones in which the writer makes herself vulnerable by exploring topics that carry a certain heft of shame, that discuss those topics we speak of usually with just the closest of friends.’

She gives an example of author Caroline Knapp’s accounts of hiding liquor bottles, drunk driving, and her obsessive relationship with her boyfriend in Drinking: A Love Story.Writing Memoirs For Readers

Nestor goes on to say, ‘These moments of shame that even the boldest memoirist can dread revealing are the very ones that memoir readers come to the page hungry for, not necessarily because they want to know every sordid detail of our lives, but because memoir readers crave the reader/author intimacy that occurs when we selectively share those moments which most of us wish to hide.

Memoir readers, perhaps more than those of any other genre, seek authenticity and companionship.’

It's Not All About Shame

However, the vulnerability we feel about publishing our memoir is not always about shame. Sometimes it's just about feeling foolish or embarrassed.

For instance, take a scene in my memoir Making the Breast of It, in which I meet Scott, the surgeon who was going to do my lumpectomy:

He’s young and fresh-faced, with blue eyes and a gentle and compassionate manner. And warm hands. I know this because I didn’t flinch as he examined my breast. (Hand temperature should be one of the criteria for entrance into medical school). In fact, if I were 30 years younger, I’d probably have a crush on him. I wonder if he’s married—thinking of my 28-year-old unattached daughter. Maybe he could be my son-in-law. But how many men could admit to having felt their mother-in-law’s breast? Forget that idea.

I thought of the reaction of readers to a 60-year-old woman ogling her young surgeon. And then I cringed when I thought of Scott reading it himself.

But I consoled myself with the fact that this was highly unlikely. And even if he did, and remembered who I was, (another very unlikely scenario), hopefully he’d be flattered, not repulsed.

Irrational? Superficial? Moi???

Another scene in my book made me feel a bit embarrassed about my irrational and somewhat superficial thinking.

I was ruminating over my mortality, (cancer tends to have that effect on you), and bemoaning the fact that because I didn’t have a wide circle of friends, I wouldn’t have many people at my funeral:

Was the number of people who attended your funeral a measure of your life’s worth, and the impact you had had on the world? If so, I had some serious work ahead of me. I needed to embark on a campaign to be more sociable and make new friends; ie going out more, maybe joining a few clubs, doing more at-home entertaining.

Then, having made these new friends, I’d have to keep in regular contact. Friends you’ve known for years (which comprise a good part of my social circle) don’t care if you only phone them once every three months, but new friendships require much more maintenance. (‘Robin who? I only met her a couple of times. She died? I won’t bother going to her funeral’).

It was written tongue-in-cheek, but there was an underlying fear. The point is, of course, that I won’t know or care when I’m dead how many people go to my funeral, but that’s the irrational nature of emotions.

Knowing that didn’t stop me being concerned about not having enough friends to make a decent showing, and thinking that if a jam-packed funeral was a measure of a life well-lived, then only having a few attendees meant that somehow, your life had been less worthy.

As someone pointed out to me, ‘All the people at the jam-packed funeral could have hated the person; they just turned up to make sure he was dead!’

You're Not Alone

The good thing about revealing your thoughts and emotions in your memoir is that you’re not alone.

I can almost guarantee that whatever you’ve thought or felt, someone else, probably many someones, will have had those very same thoughts and feelings. And they’ll be glad you’ve put them into words, because they realise they’re not alone.